A few days ago a man was elected president of the United States who claimed multiple times during the campaign that gender-affirming surgeries were being carried out in K-12 schools – in a day, no less.

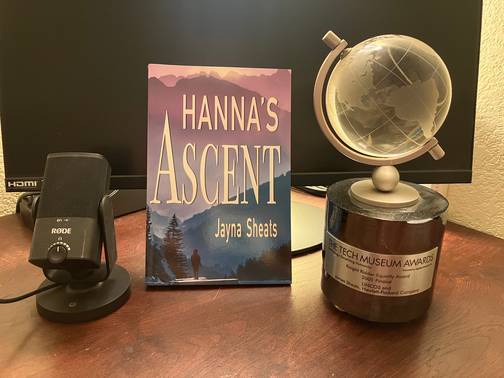

This website was created to support my creative writing, which at present consists solely of Hanna’s Ascent. That novel is centered on a transgender woman and the risk she faced of violent attack if “outed.” But social intolerance, traumatic violence, and the means of triumph over them are prominent in many contexts, and a literary novel dealing with any one has potential relevance to all.

Which brings me to the question of the hour: what role can this novel play in today’s political storm (if any)?

Quality literary art, with its enriching blend of thoughts, emotions and allusions, has at most only indirect political content. “Socialist realism” is a dreary joke at best. The author’s goal should be to expose social ills by sharply portraying them in deeply-felt human drama. Yet politics can’t always be escaped. Some of Hanna’s fiercer opponents came from the extreme wing of just one party in Germany, for example.

Tariffs and taxes are the stuff of political debate; intolerance is not. Moral failure belongs to no political party. This is why business leaders everywhere are adopting the principles of diversity, equity and inclusion. They apply with equal importance to ethnicities, races, sex and gender distinctions, disabilities, and others: they are human rights. People opposed to one of those are more likely than not to oppose the others, and anyone who cares about justice has to care about all of them. As Mr. Franklin is said to have said: “We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Though the equal human dignity of transgender people should not be partisan politics, our country has recently managed to make it so. In the just-completed campaign, more than two hundred million dollars were spent by one party on transmisic – or the linguistically incorrect but familiar “transphobic” – advertisements, while the other party defended trans rights.

So, yes: there is a role. Then: “what?”

I return to the pithy postulate of Jonathan Glazer in his Oscar acceptance speech: “…not to say ‘look what they did then’, rather ‘look what we do now’. Our film shows where dehumanization leads at its worst. It shaped all of our past and present.”

His “then” was the Holocaust. His “now” was a terrorist murder of thousands and indiscriminate “collateral damage” of tens of thousands. Can the reader not imagine any relation of those horrors to transmisia? Then it’s time for a closer look.

What they did then: U.S. Army psychologist Gustave Gilbert recounted in his book published in 1950 about the Nuremberg war criminals: “In my work with the defendants, I was searching for the nature of evil and I now think I have come close to defining it. A lack of empathy.”

What we do now: One of the president-elect’s advisors recently said in a press conference that members of the opposition party “don’t deserve any respect, you don’t deserve any empathy, and you don’t deserve any pity.”

Perhaps this (and so much more) is mere bluster. Or perhaps it’s the top of a slipperly slope ending in emulation of Uganda or Russia. LGBTQ+ people are not (yet) being put to death en masse. But no foretelling is needed to hear how rapidly this crescendo is rising. More than a year ago, a speaker at the annual conference of a large branch of the president-elect’s party proclaimed: “For the good of society… transgenderism must be eradicated from public life entirely – the whole preposterous ideology, at every level.”

Even after careful recalibration, my empathy detector isn’t seeing a signal there.

Hanna’s Ascent, like Glazer’s film, is apparently about the past but is really more about the present. The novel ends at a time when news stories about transgender people were still a rarity, and politicians didn’t think to even mention the subject. And yet the suffering in silence, the denigration that could not even be acknowledged out loud,

the quashing of her soul’s yearning over and over again, the denial of her self day after day; the menace that lurked behind friendly facades, forbidding her from ever going where she felt she belonged

is exactly what shaped the past for Hanna, and though in her personal triumph she thought she was part of a new era that had left that past behind, it is turning out to be a death-resistant zombie.

The role of the novel, therefore, is quite clear. Empathy is not a political tennis ball. It is the duty of decent people to fight anyone who denigrates, damages and even destroys others for being themselves; using the weapons they are most skilled in wielding. For Hanna and me that is this novel, and we must accept the mission.

13 Nov 2024